This time magazine article talks about the different factors that led up to the 1979 revolution and why these things were significant.

Monday, September 28, 2009

An Account of the 1953 Coup.

|

A short account of 1953 Coup Operation code-name: TP-AJAX Coup 53 of Iran is the CIA's (Central Intelligence Agency) first successful overthrow of a foreign government. But a copy of the agency's secret history of the coup has surfaced, revealing the inner workings of a plot that set the stage for the Islamic revolution in 1979, and for a generation of anti-American hatred in one of the Middle East's most powerful countries. The document, which remains classified, discloses the pivotal role British intelligence officials played in initiating and planning the coup, and it shows that Washington and London shared an interest in maintaining the West's control over Iranian oil.

The operation, code-named TP-AJAX, was the blueprint for a succession of CIA plots to foment coups and destabilize governments during the cold war - including the agency's successful coup in Guatemala in 1954 and the disastrous Cuban intervention known as the Bay of Pigs in 1961. In more than one instance, such operations led to the same kind of long-term animosity toward the United States that occurred in Iran. The history says agency officers orchestrating the Iran coup worked directly with royalist Iranian military officers, handpicked the prime minister's replacement, sent a stream of envoys to bolster the shah's courage, directed a campaign of bombings by Iranians posing as members of the Communist Party, and planted articles and editorial cartoons in newspapers. But on the night set for Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq's overthrow, almost nothing went according to the meticulously drawn plans, the secret history says. In fact, CIA officials were poised to flee the country when several Iranian officers recruited by the agency, acting on their own, took command of a pro-shah demonstration in Tehran and seized the government. Two days after the coup, the history discloses, agency officials funneled $5 million to Iran to help the government they had installed consolidate power. Dr. Donald N. Wilber, an expert in Persian architecture, who as one of the leading planners believed that covert operatives had much to learn from history, wrote the secret history, along with operational assessments in March 1954. In less expansive memoirs published in 1986, Dr. Wilber asserted that the Iran coup was different from later CIA efforts. Its American planners, he said, had stirred up considerable unrest in Iran, giving Iranians a clear choice between instability and supporting the shah. The move to oust the prime minister, he wrote, thus gained substantial popular support. Dr. Wilber's memoirs were heavily censored by the agency, but he was allowed to refer to the existence of his secret history. "If this history had been read by the planners of the Bay of Pigs," he wrote, "there would have been no such operation." "From time to time," he continued, "I gave talks on the operation to various groups within the agency, and, in hindsight, one might wonder why no one from the Cuban desk ever came or read the history." The coup was a turning point in modern Iranian history and remains a persistent irritant in Tehran-Washington relations. It consolidated the power of the shah, who ruled with an iron hand for 26 more years in close contact with the United States. He was toppled by Iranian Revolution of 1979. Later that year, "Students of Imam Line" went to the American Embassy, took diplomats hostage and declared that they had unmasked a "nest of spies" who had been manipulating Iran for decades. The Islamic government of Ayatollah Khomeini supported terrorist attacks against American interests largely because of the long American history of supporting the shah's suppressive regime. Even under more moderate rulers, many Iranians still resent the United States' role in the coup and its support of the shah. Former US Secretary of State Madeleine K. Albright, in an address, acknowledged the coup's pivotal role in the troubled relationship and came closer to apologizing than any American official ever has before. "The Eisenhower administration believed its actions were justified for strategic reasons," she said. "But the coup was clearly a setback for Iran's political development. And it is easy to see now why many Iranians continue to resent this intervention by America in their internal affairs." The history spells out the calculations to which Dr. Albright referred in her speech. Britain, it says, initiated the plot in 1952. The Truman administration rejected it, but President Eisenhower approved it shortly after taking office in 1953, because of fears about oil and Communism. The document pulls few punches, acknowledging at one point that the agency baldly lied to its British allies. Dr. Wilber reserves his most withering asides for the agency's local allies, referring to "the recognized incapacity of Iranians to plan or act in a thoroughly logical manner."

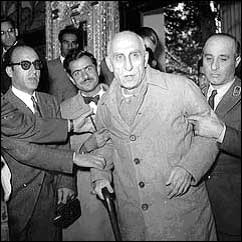

The coup had its roots in a British showdown with Iran, restive under decades of near-colonial British domination. The prize was Iran's oil fields. Britain occupied Iran in World War II to protect a supply route to its ally, the Soviet Union, and to prevent the oil from falling into the hands of the Nazis - ousting the shah's father, whom it regarded as unmanageable. It retained control over Iran's oil after the war through the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. In 1951, Iran's Parliament voted to nationalize the oil industry, and legislators backing the law elected its leading advocate, Dr. Mosaddeq, as prime minister. Britain responded with threats and sanctions. Dr. Mosaddeq, a European-educated lawyer then in his early 70's, prone to tears and outbursts, refused to back down. In meetings in November and December 1952, the secret history says, British intelligence officials startled their American counterparts with a plan for a joint operation to oust the nettlesome prime minister. The Americans, who "had not intended to discuss this question at all," agreed to study it, the secret history says. It had attractions. Anti-Communism had risen to a fever pitch in Washington, and officials were worried that Iran might fall under the sway of the Soviet Union, a historical presence there. In March 1953, an unexpected development pushed the plot forward: the CIA's Tehran station reported that an Iranian general had approached the American Embassy about supporting an army-led coup. The newly inaugurated Eisenhower administration was intrigued. The coalition that elected Dr. Mosaddeq was splintering, and the Iranian Communist Party, the Tudeh, had become active. Allen W. Dulles, the director of central intelligence, approved $1 million on April 4 to be used "in any way that would bring about the fall of Mosaddeq," the history says. "The aim was to bring to power a government which would reach an equitable oil settlement, enabling Iran to become economically sound and financially solvent, and which would vigorously prosecute the dangerously strong Communist Party." Within days agency officials identified a high-ranking officer, Gen. Fazlollah Zahedi, as the man to spearhead a coup. Their plan called for the shah to play a leading role. "A shah-General Zahedi combination, supported by CIA local assets and financial backing, would have a good chance of overthrowing Mosaddeq," officials wrote, "particularly if this combination should be able to get the largest mobs in the streets and if a sizable portion of the Tehran garrison refused to carry out Mosaddeq's orders." But according to the history, planners had doubts about whether the shah could carry out such a bold operation. His family had seized Iran's throne just 32 years earlier, when his powerful father led a coup of his own. But the young shah, agency officials wrote, was "by nature a creature of indecision, beset by formless doubts and fears," often at odds with his family, including Princess Ashraf, his "forceful and scheming twin sister." Also, the shah had what the CIA termed a "pathological fear" of British intrigues, a potential obstacle to a joint operation. In May 1953 the agency sent Dr. Wilber to Cyprus to meet Norman Darbyshire, chief of the Iran branch of British intelligence, to make initial coup plans. Assuaging the fears of the shah was high on their agenda; a document from the meeting said he was to be persuaded that the United States and Britain "consider the oil question secondary." The conversation at the meeting turned to a touchy subject, the identity of key agents inside Iran. The British said they had recruited two brothers named Rashidian. The Americans, the secret history discloses, did not trust the British and lied about the identity of their best "assets" inside Iran. CIA officials were divided over whether the plan drawn up in Cyprus could work. The Tehran station warned headquarters that the "the shah would not act decisively against Mosaddeq." And it said General Zahedi, the man picked to lead the coup, "appeared lacking in drive, energy and concrete plans." Despite the doubts, the agency's Tehran station began disseminating "gray propaganda," passing out anti-Mosaddeq cartoons in the streets and planting unflattering articles in the local press. First Few Days Look Disastrous The coup began on the night of Aug. 15 and was immediately compromised by a talkative Iranian Army officer whose remarks were relayed to Mr. Mosaddeq. The operation, the secret history says, "still might have succeeded in spite of this advance warning had not most of the participants proved to be inept or lacking in decision at the critical juncture." Dr. Mosaddeq's chief of staff, Gen. Taghi Riahi, learned of the plot hours before it was to begin and sent his deputy to the barracks of the Imperial Guard. The deputy was arrested there, according to the history, just as pro-shah soldiers were fanning out across the city arresting other senior officials. Telephone lines between army and government offices were cut, and the telephone exchange was occupied. But phones inexplicably continued to function, which gave Dr. Mosaddeq's forces a key advantage. General Riahi also eluded the pro-shah units, rallying commanders to the prime minister's side. Pro-shah soldiers sent to arrest Dr. Mosaddeq at his home were instead captured. The top military officer working with General Zahedi fled when he saw tanks and loyal government soldiers at army headquarters. The next morning, the history states, the Tehran radio announced that a coup against the government had failed, and Dr. Mosaddeq scrambled to strengthen his hold on the army and key installations. CIA officers inside the embassy were flying blind; the history says they had "no way of knowing what was happening." Mr. Roosevelt left the embassy and tracked down General Zahedi, who was in hiding north of Tehran. Surprisingly, the general was not ready to abandon the operation. The coup, the two men agreed, could still work, provided they could persuade the public that General Zahedi was the lawful prime minister. To accomplish this, the history discloses, the coup plotters had to get out the news that the shah had signed the two decrees. The CIA station in Tehran sent a message to The Associated Press in New York, asserting that "unofficial reports are current to the effect that leaders of the plot are armed with two decrees of the shah, one dismissing Mosaddeq and the other appointing General Zahedi to replace him." The CIA and its agents also arranged for the decrees to be mentioned in some Tehran papers, the history says. The propaganda initiative quickly bogged down. Many of the CIA's Iranian agents were under arrest or on the run. That afternoon, agency operatives prepared a statement from General Zahedi that they hoped to distribute publicly. But they could not find a printing press that was not being watched by forces loyal to the prime minister. On Aug. 16, prospects of reviving the operation were dealt a seemingly a fatal blow when it was learned that the shah had bolted to Baghdad. CIA headquarters cabled Tehran urging Mr. Roosevelt, the station chief, to leave immediately. He did not agree, insisting that there was still "a slight remaining chance of success," if the shah would broadcast an address on the Baghdad radio and General Zahedi took an aggressive stand. The first sign that the tide might turn came with reports that Iranian soldiers had broken up Tudeh, or Communist, groups, beating them and making them chant their support for the shah. "The station continued to feel that the project was not quite dead," the secret history recounts. Meanwhile, Dr. Mosaddeq had overreached, playing into the CIA's hands by dissolving Parliament after the coup. On the morning of Aug. 17 the shah finally announced from Baghdad that he had signed the decrees - though he had by now delayed so long that plotters feared it was too late. At this critical point Dr. Mosaddeq let down his guard. Lulled by the shah's departure and the arrests of some officers involved in the coup, the government recalled most troops it had stationed around the city, believing that the danger had passed.

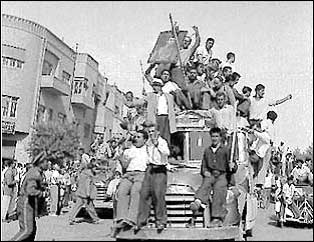

They agreed to start a counterattack on Aug. 19, sending a leading cleric from Tehran to the holy city of Qom to try to orchestrate a call for a holy war against Communism. (The religious forces they were trying to manipulate would years later call the United States "the Great Satan.") Using travel papers forged by the CIA, key army officers went to outlying army garrisons to persuade commanders to join the coup. Once again, the shah disappointed the CIA He left Baghdad for Rome the next day, apparently an exile. Newspapers supporting Dr. Mosaddeq reported that the Pahlavi dynasty had come to an end, and a statement from the Communist Party's central committee attributed the coup attempt to "Anglo-American intrigue." Demonstrators ripped down imperial statues -- as they would again 26 years later during the Islamic revolution. The CIA station cabled headquarters for advice on whether to "continue with TP-AJAX or withdraw." "Headquarters spent a day featured by depression and despair," the history states, adding, "The message sent to Tehran on the night of Aug. 18 said that 'the operation has been tried and failed,' and that 'in the absence of strong recommendations to the contrary operations against Mosaddeq should be discontinued'." CIA and Moscow Are Both Surprised

"They needed only leadership," the secret history says. And Iranian agents of the CIA provided it. Without specific orders, a journalist who was one of the agency's most important Iranian agents led a crowd toward Parliament, inciting people to set fire to the offices of a newspaper owned by Dr. Mosaddeq's foreign minister. Another Iranian CIA agent led a crowd to sack the offices of pro-Tudeh papers. "The news that something quite startling was happening spread at great speed throughout the city," the history states. The CIA tried to exploit the situation, sending urgent messages that the Rashidian brothers and two key American agents should "swing the security forces to the side of the demonstrators." But things were now moving far too quickly for the agency to manage. An Iranian Army colonel who had been involved in the plot several days earlier suddenly appeared outside Parliament with a tank, while members of the now-disbanded Imperial Guard seized trucks and drove through the streets. "By 10:15 there were pro-shah truckloads of military personnel at all the main squares," the secret history says. By noon the crowds began to receive direct leadership from a few officers involved in the plot and some who had switched sides. Within an hour the central telegraph office fell, and telegrams were sent to the provinces urging a pro-shah uprising. After a brief shootout, police headquarters and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs fell as well. The Tehran radio remained the biggest prize. With the government's fate uncertain, it was broadcasting a program on cotton prices. But by early afternoon a mass of civilians, army officers and policemen overwhelmed it. Pro-shah speakers went on the air, broadcasting the coup's success and reading the royal decrees. At the embassy, CIA officers were elated, and Mr. Roosevelt got General Zahedi out of hiding. An army officer found a tank and drove him to the radio station, where he spoke to the nation. Dr. Mosaddeq and other government officials were rounded up, while officers supporting General Zahedi placed "known supporters of TP-AJAX" in command of all units of the Tehran garrison. The Soviet Union was caught completely off-guard. Even as the Mosaddeq government was falling, the Moscow radio was broadcasting a story on "the failure of the American adventure in Iran." But CIA headquarters was as surprised as Moscow. When news of the coup's success arrived, it "seemed to be a bad joke, in view of the depression that still hung on from the day before," the history says. Throughout the day, Washington got most of its information from news agencies, receiving only two cablegrams from the station. Mr. Roosevelt later explained that if he had told headquarters what was going on, "London and Washington would have thought they were crazy and told them to stop immediately," the history states. Still, the CIA took full credit inside the government. The following year it overthrew the government of Guatemala, and a myth developed that the agency could topple governments anywhere in the world. Iran proved that third world king making could be heady. "It was a day that should never have ended," the CIA's secret history said, describing Aug. 19, 1953. "For it carried with it such a sense of excitement, of satisfaction and of jubilation that it is doubtful whether any other can come up to it."

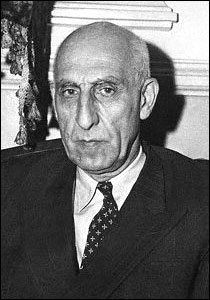

Except for Reza Shah Pahlavi founder of modern Iran and Ayatollah Rouhollah Khomeini, father of its revolution, no leader has left a deeper mark on Iran's 20th century landscape than Mohammad Mosaddeq. And no 20th century event has fuelled Iran's suspicion of the United States as his overthrow has. An eccentric European-educated lawyer whose father was a bureaucrat and whose mother descended from Persian kings, Dr. Mosaddeq served as a minister and governor before he opposed Reza Shah's accession in the 1920's. He was imprisoned and then put under house arrest at his estate in the walled village of Ahmadabad west of Tehran. Eventually he bought the village, growing crops, founding an elementary school and beginning a public health project. When Britain and Russia forced Reza Shah from power in favour of his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, in 1941, Dr. Mosaddeq became a member of Parliament. He was hailed as a hero for his fiery speeches on the evils of British control of Iran's oil industry. In 1951, when Parliament voted to nationalize the industry, the young shah, recognizing the nationalists' popularity, appointed Dr. Mosaddeq prime minister. In that job he became a prisoner of his own nationalism, unable to reach an oil compromise. Even as the British negotiated with Iran, they won the support of the major oil companies in imposing an effective global boycott on Iranian oil. Still, in the developing world Dr. Mosaddeq became an icon of anti-imperialism. He was revered despite his odd mannerisms, which included conducting business in bed in grey woollen pyjamas, weeping publicly and complaining perpetually of poor health. He amassed power. When the shah refused his demand for control of the armed forces in 1952, Dr. Mosaddeq resigned, only to be reinstated in the face of popular riots. He then displayed a streak of authoritarianism, bypassing Parliament by conducting a national referendum to win approval for its dissolution. Meanwhile, the United States became alarmed at the strength of Iran's Communist Party, which supported Dr. Mosaddeq. In August 1953, a dismissal attempt by the shah sent Dr. Mosaddeq's followers into the streets. The shah fled, amid fears in the new Eisenhower administration that Iran might move too close to Moscow. Yet Dr. Mosaddeq did not promote the interests of the Communists, though he drew on their support. Paradoxically, the party turned from him in the end because it viewed him as insufficiently committed and too close to the United States. By the time the royalist coup overthrew him after a few chaotic days, he had alienated many landowners, clerics and merchants.

When the revolution brought the clerics to power in 1979, anti-shah nationalists tried to revive Dr. Mosaddeq's memory. A Tehran thoroughfare called Pahlavi Avenue was renamed Mosaddeq Avenue. But Ayatollah Khomeini saw him as a promoter not of Islam but of Persian nationalism, and envied his popularity. So Mosaddeq Avenue became Vali Asr, after the revered Hidden Imam, whose reappearance someday, Shiite Muslims believe, will establish the perfect Islamic political community. Still, even Ayatollah Khomeini was careful not to go too far. Ignoring Dr. Mosaddeq, rather than excoriating him, became the rule. Two decades later, the Mosaddeq cult has been revitalized by resurgent nationalism and frustration with the strictures of Islam. Dr. Mosaddeq inspires the young, who long for heroes and have not necessarily found them, either in clerics or kings. In campaigns for local elections in February 1999 and parliamentary elections a year later, reformist advertising made use of Dr. Mosaddeq's sad, elongated face. And every year since his death, his supporters have rallied at his estate. His legacy still stirs considerable debate. In August, Parliament approved a bill to abolish a holiday marking the nationalization of the oil industry in 1951. The decision set off protests in the press "Alas! Parliament ignored the most apparent symbol of the struggle of the Iranian people throughout history against colonialism," the reformist daily Khordad said. In November, legislators were forced to reinstate the holiday. CIA Tried, With Little Success, to Use U.S. Press in Coup Central Intelligence Agency officials plotting the 1953 coup in Iran hoped to plant articles in American newspapers saying Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's return resulted from a home-grown revolt against a Communist-leaning government, internal agency documents show. Those hopes were largely disappointed. The CIA's history of the coup shows that its operatives had only limited success in manipulating American reporters and that none of the Americans covering the coup worked for the agency. An analysis of the press coverage shows that American journalists filed straightforward, factual dispatches that prominently mentioned the role of Iran's Communists in street violence leading up to the coup. Western correspondents in Iran and Washington never reported that some of the unrest had been stage-managed by CIA agents posing as Communists. And they gave little emphasis to accurate contemporaneous reports in Iranian newspapers and on the Moscow radio asserting that Western powers were secretly arranging the shah's return to power. It was just eight years after the end of World War II, which left American journalists with a sense of national interest framed by six years of confrontation between the Allies and the Axis. The front pages of Western newspapers were dominated by articles about the new global confrontation with the Soviet Union, about Moscow's prowess in developing nuclear weapons and about Congressional allegations of "Red" influence in Washington. In one instance, the history indicates, the CIA was apparently able to use contacts at The Associated Press to put on the news wire a statement from Tehran about royal decrees that the CIA itself had written. But mostly, the agency relied on less direct means to exploit the media. The Iran desk of the State Department, the document says, was able to place a CIA study in Newsweek, "using the normal channel of desk officer to journalist." The article was one of several planted press reports that, when reprinted in Tehran, fed the "war of nerves" against Iran's prime minister, Mohammad Mosaddeq. The history says the Iran operation exposed the agency's shortcomings in manipulating the American press. The CIA "lacked contacts capable of placing material so that the American publisher was unwitting as to its source." The history discloses that a CIA officer, working under cover as the embassy's press officer, drove two American reporters to a house outside Tehran where they were shown the shah's decrees dismissing the prime minister. Kennett Love, the New York Times reporter in Tehran during the coup, wrote about the royal decrees in the newspaper the next day, without mentioning how he had seen them. In an interview, he said he had agreed to the embassy official's ground rules that he should not report the American role in arranging the trip. Mr. Love said he did not know at the time that the official worked for the CIA. After the coup succeeded, Mr. Love did in one article briefly refer to Iranian press reports of American involvement, and The New York Times also published an article from Moscow reporting Soviet charges that the United States was behind the coup. But neither The Times nor other American news organizations appear to have examined such charges seriously. In a 1960 paper he wrote while studying at Princeton University, Mr. Love explained that he "was responsible, in an impromptu sort of way, for speeding the final victory of the royalists." Seeing a half-dozen tanks parked in front of Tehran's radio station, he said, "I told the tank commanders that a lot of people were getting killed trying to storm Dr. Mosaddeq's house and that they would be of some use instead of sitting idle at the radio station." He added, "They took their machines in a body to Kakh Avenue and put the three tanks at Dr. Mosaddeq's house out of action." Mr. Love, who left The New York Times in 1962, said in an interview that he had urged the tanks into action "because I wanted to stop the bloodshed." Months afterward, Mr. Love says, he was told by Robert C. Doty, then Cairo bureau chief and his boss, of evidence of American involvement in the coup. But Mr. Doty, who died in 1974, did not write about the matter, and by the summer of 1954, Mr. Love decided to tell the New York office what he knew. In a July 26, 1954, letter to Emanuel R. Freedman, then the foreign editor, Mr. Love wrote, "The only instance since I joined The Times in which I have allowed policy to influence a strict news approach was in failing to report the role our own agents played in the overthrow of Mosaddeq." Mr. Love said he had hoped that the foreign editor would order him to pursue the subject. But he never received any response, he said. "I wanted to let Freedman know that I knew there had been U.S. involvement in the coup, but that I hadn't written about it," he said. "I expected him to say, 'Jump on that story.' But there was no response." Mr. Freedman died in 1971. 'Gentleman Spy' Donald Wilber, who planned the coup in Iran and wrote its secret history, was old-school CIA, a Princetonian and a Middle East architecture expert who fit neatly into the mold of the "gentleman spy." Years of wandering through Middle Eastern architectural sites gave him the perfect cover for a clandestine life. By 1953, he was an obvious choice as the operation's strategist. The coup was the high point of his life as a spy. Although he would excel in academia, at the agency being part-time was a handicap. "I never requested promotion, and was given only one, after the conclusion of AJAX," Dr. Wilber wrote of the Iran operation. On his last day, "I was ushered down to the lobby by a young secretary, turned over my badge to her and left." He added, "This treatment rankled for some time. I did deserve the paperweight." Donald Wilber died in 1997 at 89. taken from Iran Chamber Society http://www.iranchamber.com/history/coup53/coup53p3.php |

Sunday, September 13, 2009

The Qajars, The Shah, and the Constitutional Revolution

Constitutional Revolution

During the early 1900s the only way to save country from government corruption and foreign manipulation was to make a written code of laws. This sentiment caused the Constitutional Revolution. There had been a series of ongoing covert and overt activities against Naser o-Din Shah’s despotic rule, for which many had lost their lives. The efforts of freedom fighters finally bore fruit during the reign of Moazaferedin Shah. Mozafaredin shah ascended to throne on June 1896. In the wake of the relentless efforts of freedom fighters, Mozafar o-Din Shah of Qajar dynasty was forced to issue the decree for the constitution and the creation of an elected parliament (the Majlis) in August 5, 1906. The royal power limited and a parliamentary system established.

|

| Bakhtiari Revolutionaries in camp outside Esfahan (June 1909) In front, in a white coat with a sword, is Mohammad Ebrahim Khan, Zabet of Julfa. |

On August 18, 1906, the first Legislative assembly (called as Supreme National Assembly), was formed in the Military Academy to make the preparations for the opening of the first Term of the National Consultative Assembly and drafting the election law thereof. During this meeting, Prime Minister Moshirul Doleh delivered a speech as the head of the cabinet. The session concluded with the address made by Malek Al Motokalemin.

On October 7th, 1906 in a speech made in spite of his poor health, Mozaferedin Shah inaugurated the first session of the National Consultative Assembly. At this time the session was formed in the absence of representatives from provinces.

Following Mozafaredin Shah’s death, his successor, Mohammad Ali Mirza who was then ruled Tabriz as a crown prince, ascended to the throne on January 21st, 1907. Before taking the reign, he pledged to respect the fundaments of Constitution and Nation’s Rights. But he contravened this from the very beginning which made Constitutionalists to react.

Capitalizing on the internal struggles, both Russia and Britain entered a pact to settle their own differences; effectively dividing Iran into two areas of influence for their respected countries. This made headlines in early September 1907 and united the various factions in Iran. The Iranian government was officially notified of this pact on September 7, 1907 by Russian and British Ambassadors.

The rising tides of dissatisfaction and discontent caused Mohammad Mirza to summon the cabinet members on December 17, 1907 under the false pretense of soliciting advice. He immediately orders their detention. Only Nasserul Molk, who was the prime minister, was let free.

On December 22, 1907 a new cabinet was formed headed by Nezamul Saltaneh Mafi. On the surface the air is cleared and the tensions are eased. But on February 1908, a bomb is thrown at Shah’s Coach, making him highly suspicious. On June 1st, 1908 Shah purges some of the courtiers. Ambassador Zapolski of Russia and Ambassador Marling of Britain warn the Iranian Government to submit to Shah’s intents.

|

| Freedom Fighters of Tabriz The two men in the center are Sattar Khan & Bagher Khan. |

During these times, the Tabriz uprising culminated and within the span of four months spread to Rasht, Qazvin, Esfahan, Lar, Shiraz, Hamadan,Mashhad, Astar-Abad, Bandar Abbas andBushehr. The Freedom fighters prevailed against the tyranny at all points. Yet Tabriz was still under economic and military blocked set up by government forces.

On February 17, 1909, Freedom Forces captured Rasht. By March, they succeed in taking control of Rasht and Qazvin main roads. By April 22nd, 1909, Tabriz Freedom Fighters under the leadership of Sattar Khan(Sardar-e Meli) made their attack to break through the blockade. They lost huge number of their fighters. An English Reporter named Moore and an American Missionary called Howard Baskerville, who were sympathetic with the freedom fighters were killed.

Commanded by General Yeprim and Brigadier Mohi, freedom fighters of Rasht occupied Qazvin and advanced towards Tehran.

On June 22, 1909, Bakhtiari Chieftains, led by Samsam-ul-Saltaneh and Haj Aligholi Khan Bakhtiari (Sardar As’ad) reached the city of Qum, which they took over on July 8th,1909. The intimidations and interventions made by Russian and British embassies failed to stop the advance of freedom fighters. Inevitably, a number of Russian troops were dispatched to Gilan via Badkobeh, reaching Qazvin on July 12th, 1909. Russians warned Gilan Fighters to stop moving in against Tehran.

|

| A nationalist council at Rasht |

On July 16, 1909, the capital was under complete control of freedom fighters. At 8:30, on the morning of July 17, 1909, Mohammad shah and a number of his supporters, under armed escort of Russian soldiers, took asylum with Russian Embassy in Zargandeh.

On this very day, the National Consultative Assembly (Majlis) held an emergency session and deposed Mohammad Ali Shah as a monarch, and named his 13 year old son, Ahmad Mirza as his successor. Azadulmolk was named as the Vice-Regent.

On September 10th, 1909, Mohammad Ali Shah left the Russian Embassy and went into exile in Russia.

First Term (October 7th, 1906 – June 23rd, 1908)

The most important task undertaken by the first Majlis was drafting and ratification of the Constitution on December 30th, 1906. It also set out the internal procedures. On October 17th, 1907 it drafted and ratified the constitutional amendments.

The first Majlis was dissolved before the end of its Term due to Mohammad Ali Shah’s opposition against the Constitutionalists as well as foreign intrigues. Colonel Liakhov, the Russian commander of the Iranian Cossack brigade, along with several Russian officers set artillery fire against Majlis. A number of Majlis Representatives and Constitutionalists were detained in Bagh Shah, of which a number were killed. Some fled to and sought asylum with foreign embassies. Thus the First Majlis was dissolved and a martial law was declared.

Second Term (November 15th, 1909 – December 24th, 1911)

The second Majlis came into session after a period of Interregnum that lasted almost 17 months. A two-stage, indirect plebiscite was carried out. Confronted with severe crises and dilemmas arising from interventions by foreign forces and domestic hardships, Majlis stood its ground as far as possible. Finally it was dissolved under foreign pressure. The representatives either fled or went into exile.

Nevertheless important bills were passed during this time. These included the Public Tax Act, Bureau of Audit Act, the new election law, and the Education Bill.

Third Term (December 6th, 1914 – December 14th, 1915)

The Third Majlis did not last more than a year. Faced with the First Word War, Majlis representatives declared Iran’s neutrality. Nevertheless, Iran’s neutrality was blatantly transgressed by foreign expeditionary forces. The Czarist Russian Army expeditionary force left Qazvin for Tehran, bringing up the question of relocating the capital. It raised concerns and led to riots. A number of representatives moved to Qum and from there to Kermanshah. Majlis session could not be held due to lack of quorum. It finally adjourned in November 12th, 1915.

During this period, Majlis approved important laws such as the Military Conscription Act, Ministry of Finance constitution bill, and Real Estate tax law.

Fourth Term (June 21st, 1921 – June 20th, 1923)

Following a long interregnum , that lasted five years and seven months), the Fourth Majlis was inaugurated. Most of its time had been spent in tension and rancor.

The most valuable action taken was when it drafted and approved a bill submitted by Majlis majority leader Seyyed Hassan Modaress. The bill called for the abolition of the 1919 accord, signed between the Iranian Prime Minister and the British Government without Majlis knowledge. The accord had been put into effect before Majlis had any chance on debating it.

Moddares’ bill, once approved, was announced publicly and the British government was formally notified.

The most important legislations passed during this period had been:

Fifth Term (February 11th, 1924 – February 11th, 1924)

One of the tumultuous periods in Majlis, when a combination of generalissimo and foreign influence joined forces to put an end to the Qajar Dynasty. Independent Majlis representatives were harassed, intimidated and even assassinated in order to have the Minister of War, Reza Khan, installed to the throne.

Some of the important bills and legislations approved by Majlis during this period were:

Sixth Term (July 10th, 1926 – August 13th, 1928)

The most important event during this period had been the abolition of Capitulation on May 9th, 1927.

Some of the important bills and legislations approved by Majlis during this period were:

Seventh Term (October 6th, 1928 – November 5th, 1930)

Majlis granted the right of issuing currency to the Iran National Bank (Bank Melli Iran). This task used to be carried out by Iran Royal Bank.

Among the important bills and legislations approved by Majlis during this period were:

Eight Term (December 15th, 1930 – January 14th, 1933)

During this period the Minister of Treasury proposed that Darcy License , which monopolized the Iranian oil fields, be cancelled.

The most important bills passed by Majlis at this time were:

Ninth Term (March 15th, 1933 – April 10th, 1935)

The period saw negotiations with the British government over petroleum. It led to a new agreement. The Tehran University was inaugurated on February 4th, 1936.

Some of the most important legislations were:

Tenth Term (June 6th, 1935– June 12th, 1937)

The most important event during this period had been negotiations for the signing of non-aggression pact between Iran, Afghanistan, Turkey and Iraq.

The most important legislations ratified were:

Eleventh Term (September 11th, 1937 – September 18th, 1939)

The Second World War conflagrated at this time. Iran proclaimed its neutrality in the conflict.

Among the important bills and legislations approved by Majlis during this period were:

Twelfth Term (October 25th, 1940– October 30th, 1941)

Numerous social and economic problems arising from the Second World War gripped the country. While Iran had declared its neutrality, Soviet Union and Britain blatantly disregarded it and sent in their troops into Iran under the pretext of supposed Reich influence in Iran.

During an emergency session on September 17, 1941, Reza Shah abdicated in favor of his son, Mohammad Reza who was sworn in as the new monarch on the next day. Meanwhile with the Generalissimo Reza Khan out of the way, Majlis passed a bill of pardon and clemency for a number of political and general sentences.

Thirteenth Term (November 13th, 1941 – November 23rd, 1943)

This period coincided with the Tehran Conference attended by the head of states of Britain, Soviet Union and United States, where the territorial integrity and political independence of Iran was guaranteed.

Important bills and legislations approved during this period were:

Taken from the Iran Chamber Society:

http://www.iranchamber.com/history/constitutional_revolution/constitutional_revolution.php

The Qajar Dynasty

Qajar Dynasty

Fath Ali Shah, 1797 - 1834 Under Fath Ali Shah, Iran went to war against Russia, which was expanding from the north into the Caucasus Mountains, an area of historic Iranian interest and influence. Iran suffered major military defeats during the war. Under the terms of the Treaty of Golestan in 1813, Iran recognized Russia's annexation of Georgia and ceded to Russia most of the north Caucasus region. A second war with Russia in the 1820s ended even more disastrously for Iran, which in 1828 was forced to sign the Treaty of Turkmanchai acknowledging Russian sovereignty over the entire area north of the Aras River (territory comprising present-day Armenia and Republic of Azerbaijan). Fath Ali's reign saw increased diplomatic contacts with the West and the beginning of intense European diplomatic rivalries over Iran. His grandson Mohammad Shah, who fell under the influence of Russia and made two unsuccessful attempts to capture Herat, succeeded him in 1834. When Mohammad Shah died in 1848 the succession passed to his son Naser-e-Din, who proved to be the ablest and most successful of the Qajar sovereigns.

During Naser o-Din Shah's reign Western science, technology, and educational methods were introduced into Iran and the country's modernization was begun. Naser o-Din Shah tried to exploit the mutual distrust between Great Britain and Russia to preserve Iran's independence, but foreign interference and territorial encroachment increased under his rule. He contracted huge foreign loans to finance expensive personal trips to Europe. He was not able to prevent Britain and Russia from encroaching into regions of traditional Iranian influence. In 1856 Britain prevented Iran from reasserting control over Herat, which had been part of Iran in Safavid times but had been under non-Iranian rule since the mid-18th century. Britain supported the city's incorporation into Afghanistan; a country Britain helped create in order to extend eastward the buffer between its Indian territories and Russia's expanding empire. Britain also extended its control to other areas of the Persian Gulf during the 19th century. Meanwhile, by 1881 Russia had completed its conquest of present-day Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, bringing Russia's frontier to Iran's northeastern borders and severing historic Iranian ties to the cities of Bukhara and Samarqand. Several trade concessions by the Iranian government put economic affairs largely under British control. By the late 19th century, many Iranians believed that their rulers were beholden to foreign interests. Mirza Taghi Khan Amir Kabir, was the young prince Nasser o-Din's advisor and constable. With the death of Mohammad Shah in 1848, Mirza Taqi was largely responsible for ensuring the crown prince's succession to the throne. When Nasser o-Din succeeded to the throne, Amir Nezam was awarded the position of prime minister and the title of Amir Kabir, the Great Ruler. Iran was virtually bankrupt, its central government was weak, and its provinces were almost autonomous. During the next two and a half years Amir Kabir initiated important reforms in virtually all sectors of society. Government expenditure was slashed, and a distinction was made between the privy and public purses. The instruments of central administration were overhauled, and the Amir Kabir assumed responsibility for all areas of the bureaucracy. Foreign interference in Iran's domestic affairs was curtailed, and foreign trade was encouraged. Public works such as the bazaar in Tehran were undertaken. Amir Kabir issued an edict banning ornate and excessively formal writing in government documents; the beginning of a modern Persian prose style dates from this time. One of the greatest achievments of Amir Kabir was the building of Dar-ol-Fonoon, the first modern university in Iran. Dar-ol-Fonoon was established for training a new cadre of administrators and acquainting them with Western techniques. Amir Kabir ordered the school to be built on the edge of the city so it can be expanded as needed. He hired French and Russian instructors as well as Iranians to teach subjects as different as Language, Medicine, Law, Georgraphy, History, Economics, and Engeneering. Unfortunatelly, Amir Kabir did not live long enough to see his greatest monument completed, but it still stands in Tehran as a sign of a great man's ideas for the future of his country. These reforms antagonized various notables who had been excluded from the government. They regarded the Amir Kabir as a social upstart and a threat to their interests, and they formed a coalition against him, in which the queen mother was active. She convinced the young shah that Amir Kabir wanted to usurp the throne. In October 1851 the shah dismissed him and exiled him to Kashan, where he was murdered on the shah's orders.

When Naser o-Din Shah was assassinated by Mirza Reza Kermani in 1896, the crown passed to his son Mozaffar o-Din. Mozaffar o-Din Shah was a weak and ineffectual ruler. Royal extravagance and the absence of incoming revenues exacerbated financial problems. The shah quickly spent two large loans from Russia, partly on trips to Europe. Public anger fed on the shah's propensity for granting concessions to Europeans in return for generous payments to him and his officials. People began to demand a curb on royal authority and the establishment of the rule of law as their concern over foreign, and especially Russian, influence grew. The shah's failure to respond to protests by the religious establishment, the merchants, and other classes led the merchants and clerical leaders in January 1906 to take sanctuary from probable arrest in mosques in Tehran and outside the capital. When the shah reneged on a promise to permit the establishment of a "house of justice", or consultative assembly, 10,000 people, led by the merchants, took sanctuary in June in the compound of the British legation in Tehran. In August the shah was forced to issue a decree promising a constitution. In October an elected assembly convened and drew up a constitution that provided for strict limitations on royal power, an elected parliament, or Majles, with wide powers to represent the people, and a government with a cabinet subject to confirmation by the Majles. The shah signed the constitution on December 30, 1906. He died five days later. The Supplementary Fundamental Laws approved in 1907 provided, within limits, for freedom of press, speech, and association, and for security of life and property. The Constitutional Revolution marked the end of the medieval period in Iran. The hopes for constitutional rule were not realized, however. Mozaffar o-Din's son Mohammad Ali Shah (reigned 1907-09), with the aid of Russia, attempted to rescind the constitution and abolish parliamentary government. After several disputes with the members of the Majlis, in June 1908 he used his Russian-officered Persian Cossacks Brigade to bomb the Majlis building, arrest many of the deputies, and close down the assembly. Resistance to the shah, however, coalesced in Tabriz, Esfahan, Rasht, and elsewhere. In July 1909, constitutional forces marched from Rasht and Esfahan to Tehran, deposed the shah, and re-established the constitution. The ex-shah went into exile in Russia.

Ahmad Shah, was born 21 January 1898 in Tabriz, who succeeded to the throne at age 11, proved to be pleasure loving, effete, and incompetent and was unable to preserve the integrity of Iran or the fate of his dynasty. The occupation of Iran during World War I (1914-18) by Russian, British, and Ottoman troops was a blow from which Ahmad Shah never effectively recovered. With a coup d'état in February 1921, Reza Khan (ruled as Reza Shah Pahlavi, 1925-41) became the preeminent political personality in Iran; Ahmad Shah was formally deposed by the Majles (national consultative assembly) in October 1925 while he was absent in Europe, and that assembly declared the rule of the Qajar dynasty to be terminated. Ahamd Shah died later on 21 February 1930 in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France. Taken from the Iranian Chamber Society Website :http://www.iranchamber.com/history/constitutional_revolution/constitutional_revolution.php |

Tuesday, September 1, 2009

Waitlisted Students

So I spoke to the person in charge of class sizes. She's increased the class size by 10 for both the upper division and lower division sections and those of you on the wait-list should be moved in to the class by now.

Feel free to shoot me an email any hour of the day and I'll do my best to get back to you as soon as possible.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)